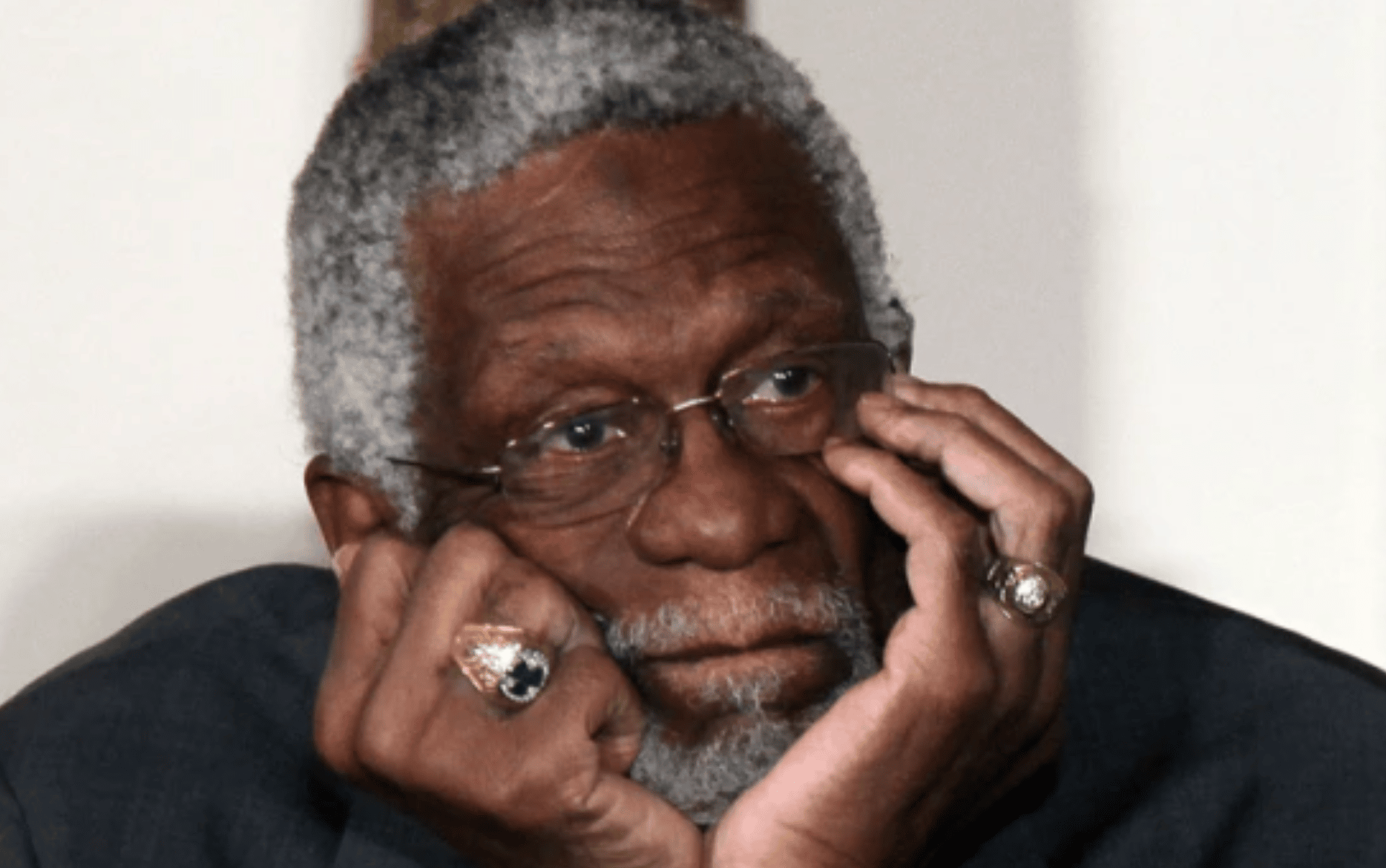

Bill Russell, the intimidating center who rejected layups and bigotry with equal authority while leading the Boston Celtics to pro basketball’s greatest dynasty, died Sunday, his family announced. He was 88.

Russell won five Most Valuable Player awards and the Celtics captured 11 NBA championships during his 13-year career, including eight in a row from 1959-66. His powerful adversary during the 1960s, Wilt Chamberlain, ended the streak by leading the Philadelphia 76ers to the league title.

The 7-foot-1 Chamberlain and the 6-foot-9 Russell met 142 times in an epic rivalry of big men that riveted basketball fans for a decade. His Celtics went 57-37 against Chamberlain’s teams during the regular season and owned a 29-20 advantage in the playoffs.

“Wilt and Russell were to basketball what Arnold Palmer was to golf,” 76ers Hall of Fame forward Billy Cunningham once said. “Turn on the television on Sunday, and there they were. They are the two greatest talents to ever play the game.”

While establishing himself as pro basketball’s ultimate winner, Russell was a powerful advocate for civil rights. At the ESPYs in 2019, he received the Arthur Ashe Courage Award, given annually to those who “stand up for their beliefs, no matter what the cost.”

Russell’s experiences growing up impoverished in Oakland, California, shaped his intolerance of racism. Even as an established NBA star, he still found himself grappling against bigotry on an everyday basis. When the Celtics were on the road, their Black players routinely were denied the same housing and restaurant meals offered to the rest of the team.

After leading the Celtics to their initial championship as a rookie in 1956-57, Russell moved his family to Reading, Massachusetts, 16 miles north of Boston. A few years later, vandals broke into his home, destroying his trophies and defecating in his bed.

When the Celtics retired Russell’s No. 6 before a home game against the New York Knicks in 1972, he insisted on a brief, private ceremony to be staged an hour before fans were allowed in the building. In his 1979 memoir, Second Wind, he labeled Boston “a flea market of racism.”

“Bill is a proud man who has been offended by a racist society, and he won’t give an inch to it,” former Celtics teammate Bob Cousy once said. “So it is obvious that Russ always had a very strong chip on his shoulder, and he demonstrated that to the outside world at every opportunity. His public persona was to thumb his nose at whitey.”

The thoughtful Russell participated in the March on Washington in 1963 and invested in a program to purchase rubber plantations in Liberia to create jobs in African nations. And in 1967, he participated alongside Jim Brown, Lew Alcindor (now Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) and other athletes in a news conference to support Muhammad Ali’s refusal to be drafted into the service.

“Bill Russell didn’t wait until he was safe to stand up for what was right,” said late Georgetown coach John Thompson, another onetime Celtics teammate. “He represented things that were right while he had something to lose.”

Despite his fame, Russell refused to sign autographs and often seemed aloof to Boston fans. Instead of courting public acclaim, he focused on defense, rebounding — he once had 51 rebounds in a game — and winning championships under legendary coach Red Auerbach.

(Excerpt) Read more in: The Hollywood Reporter